Breach of Promise (1982)

"Breach of Promise," FILE Megazine, Spring, 1982, pp 36-37. Republished in Struggles with the Image: Essays in Art Criticism, Toronto: YYZ Books, 1988.

A notebook deposited with Philip Monk’s papers at the National Gallery of Canada shows that this text started in July-August 1981 as an idea for a film in the style of Marguerite Duras’s India Song. For this notebook excerpt, click here.

Click to read original article

BREACH OF PROMISE

Death, as we may call that unreality, is the most terrible thing, and to keep and hold fast what is dead demands the greatest force of all.

—Hegel

In effect, nothing is less animal than the fiction, more or less removed from reality, of death.

—Bataille

It should be spoken, as if standing in front of a painting, as if in fascination bending forward to capture a detail led to a fall.

It should be spoken, as if a fright rose and lodged itself in the throat, as if death’s sex brushed you from behind.

It should be spoken, as if speech could save you from this terror that the eye registers in its primitive state.

A face and head turn, “as if speaking to the other, in rivalry, in anxiety, for recognition.”

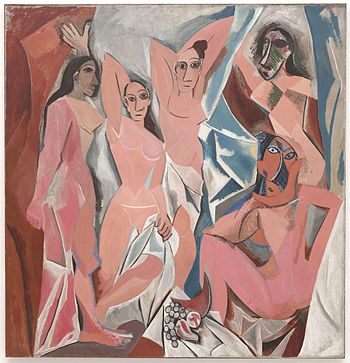

What is it, what by chance attracts me to these images? What solicits my attention to each and to the pair? Across a gap of centuries, they answer to each other in my attention. Projected into each other through a correspondence of poses, each is the unconscious of the other, the unspoken. What could not be said in its time is given a history in my encounter.

Why was this choice presented to me, a necessity more than a formal similarity? How do I figure in this choice? What absences signify my presence there more than the unfilled gap in the Michelangelo painting? My presence and absence.

In the presentation of the spectacle, what is offered to me? A gift that is poison. What is offered, a gift that poisons sight. What I do not want to know, what I do not want to face.

Two images beside each other, these images by men, face me. In my position as mediator, what attracts and follows is my complicity as a man—specular and speculative.

The passage from one image to the other, from The Entombment to The Demoiselles, is a narrative transformation: from the presence of promise to its absence. On my side, the narrative is the representation of fascination—putting its drives into motion. To represent the ‘breach’ between the two images—the breach and the space between—is to register the gap between me and them. Representation leaves an absence in its origin.

The narrative I fabricate at first is compensation for a loss I feel in front of these images. But the movement from one to the other, controlled by the narrative itself, repels my compensation, rejects the insistence of my demands. The narrative is projected as a loss; its history is figured as a loss. How do I sustain that recognition, the refusal of my compensation?

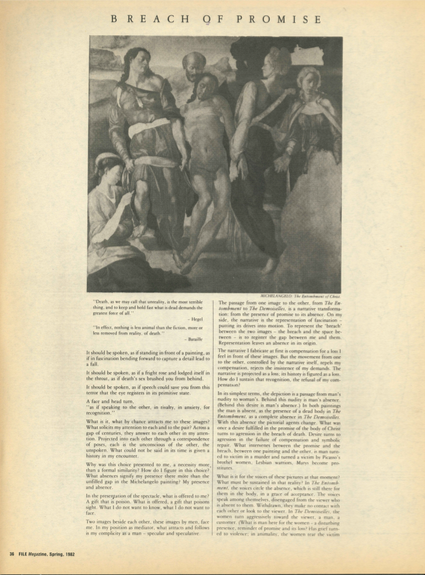

In its simplest terms, the depiction is a passage from man’s nudity to woman’s. Behind this nudity is man’s absence. (Behind this desire is man’s absence.) In both paintings the man is absent, as the presence of a dead body in The Entombment, as a complete absence in The Demoiselles. With this absence the pictorial agents change. What was once a desire fulfilled in the promise of the body of Christ turns to aggression in the breach of death. Desire turns to aggression in the failure of compensation and symbolic repair. What intervenes between the promise and the breach, between one painting and the other, is man turned to victim in a murder and turned a victim by Picasso’s brothel women, Lesbian warriors, Marys become prostitutes.

What is it for the voices of these pictures at that moment? What must be sustained in that reality? In The Entombment, the voices circle the absence, which is still there for them in the body, in a grace of acceptance. The voices speak among themselves, disengaged from the viewer who is absent to them. Withdrawn, they make no contact with each other or look to the viewer. In The Demoiselles, the women turn aggressively toward the viewer, a man, a customer. (What is man here for the women—a disturbing presence, reminder of promise and its loss? Has grief turned to violence; in animality, the women tear the victim apart? Or is woman’s position and antagonistic gaze one of social violence?)

The spectator is not necessary to the Michelangelo painting; although he can observe, he is closed to that drama, discreet and distanced. The man is absent in the Picasso painting, but the spectator is structurally demanded—forcibly excluded by the gazes, but demanded to fill an absent place. How does man return here in his absence? Are the women simply and solely the object of his gaze substituted by the spectator?

Absence at its most invested is abandonment or murder. It is never an empty or neutral figure. Whatever it is, a position is maintained, whether inflected towards absence or another presence. And that absence is simple or mediated—simple as the immediate effects of murder or abandonment—a tearing; mediated, as representation. Recognized absence becomes represented. Recognition is a tableau. But whether the two poles of response to absence are acceptance or aggression, that is, symbolic or actual, representational or violent, the end is representation: the victim torn apart by the women is recreated in absence as a ritual and representation.

But the absence for me reflected in these works, my absence, is not a representation. It is a loss.

The mask plays a role in the look. Representation is a violence of and by the mask.

That which is faced or held in death is the horror of the mask. The violence to the mask is the violence of the mask. The violence of the mask, the violence to the mask is the violence of the mark. Facing me, it calls for my violence to match its own. But for me here in front of this painting, it is not a question of facing or wearing a mask; it is woman and the mask. Beyond nudity and the mask, nudity and death, it is the mask and woman’s nudity—my desire and woman’s nudity.

Facing and turning. I turn from the spectacle. I avert my gaze. I turn from a conversation. At another time I turn towards a landscape. I turn from the icon, this image, this face.

The icon is opposed to the group, as desire is to civility, as the gaze is to conversation—in a play between violence and civility, between desire and culture. How does civility become violence, turn and transform culture back to nature?

Here the landscape opens; there the icon marks a closure, a limit and marking of my desire.

My figure at that moment of facing is taut, collapsing within, like the tensile arch of the figures supporting the body of Christ, a play between the arch of the bodies and the limp, dead body. Like a veil, and as the female, the paintings open to reveal the dead object at the base of woman’s sex. They open to disclose the male. The male can only be absent. Dead or excluded, he projects himself into that absence in the painting. And he projects himself through the violence of exclusion. What is the object of man’s gaze if it is not his own absence? Woman is not the object of his gaze. It is not a single object, but the schema. His gaze is aggressive if excluded, but it is also dissolute and frenzied in a forced absence. In that exclusion, he wishes the immediacy and presence of a violent sexuality, death itself. The gaze is not possessive but destructive: the other is destroyed as a surrogate for himself. Destruction is figured as the women of The Demoiselles, what the man of mastery desires and is not.

The original promise transforms in a binding effect. So as the promise turns, disappears or is spoiled, the recipient turns and is transformed in despair.

The breach of promise is a breaking of the symbolic: the breach strands me in the gap between these two images.

The willed turn in the breach of promise is no compensation. Compensation is a lure and maintenance of the symbolic. “Compensation is a rhythm,” she said. And so is art. Beyond compensation, in that indifference, either death or aggression face me. To hold fast what is dead, beyond that promise, is to face that unreality. What is it for the voices at that moment? What must be sustained in that reality, unreality?

MICHELANGELO: The Entombment of Christ

PICASSO: Les Demoiselles d'Avignon