Becoming American: Play of Identification in Robert Frank's The Americans

This is an unpublished text written, I think, in 1999, perhaps earlier. The notes are incomplete.

Becoming American

“There is only one thing you should not do, criticize anything. The Americans are extremely proud of their country!”

Robert Frank, letter to parents, March 1947 [1]

The fact that Robert Frank's The Americans was so immediately influential on photographers counteracted its first generally negative—even hostile—critical reception. This practical success ensured that the volume would retain its printed life whereby the judgements of successive generations of readers would declare it a classic. To be a classic is to sustain more than the judgement of generations: a work must speak variously to its readers over time. "Speaking to" an audience is only another way of saying the audience sees itself in a work by way of its portrayal. That portrayal, however, may incite instead a negative identification to the images proferred: "We are not that!"

Such were the first reactions in America. They were moulded already, perhaps, by the 1958 French publication with its anti-American texts juxtaposed to Frank's photographs, weighty captions inflecting Frank's images as a negative critique. The first American reviews, and those by the editors of the May 1960 Popular Photography are a handy summary, were critical of Frank's selective view of America. For the most part, the book, and its presumptive title especially, provoked vitriolic responses from the reviewers. They saw the photographs as a perverse, hateful, and juvenile attack on America that showed the country's worst aspects through a warped objectivity similar to thirties' propaganda. Because of its association with Kerouac—he wrote the Introduction—it was seen to be a beat book, but contrary to the enthusiasms of Kerouac, loveless, yet, all the same, sharing that writer's flaunting of craft.

Even the plain descriptive captions citing place alone were criticized as being tongue-in-cheek. "Irony" soon would become the pivot around which interpretations eventually would swing, whether that irony was recognized as juxtaposition within the frame of the individual photograph or between them in their narrative sequence. At the same time as its hostile reception, Walker Evans in 1958 could speak more positively of this irony: "He shows high irony towards a nation that generally speaking has it not; adult detachment towards the more-or-less juvenile section of the population that came into view."[2] The ensuing set of interpretations was not so much a reversal of meaning as a reversal of value given to it: Frank’s supposedly critical and ironic vision of America was not attacked but accepted as prescient. As one author still hostile, however, in 1974, wrote: "During the 60s, as the old happy lies about America blew up in faces, Frank's vision suddenly made perfect sense. This was what he had seen in the mid-50s—a fragmented greedy people—and this was what the documentary photographers of the 60s—Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, Danny Lyon, Garry Winogrand—almost compulsively showed us. The Beat Generation's wise-guy nihilism was adopted by the hippies and the radical youth; but Frank's influence went further: his way of seeing changed—expanded—the way most educated Americans saw their country."[3]

The play of identification, for and against, is the dynamic that has sustained the book's meaning over the years. This has become especially evident on the occasions for re-evaluating The Americans that subsequent printings and exhibitions have offered. With his current retrospective, Robert Frank: Moving Out; and a travelling exhibition devoted to The Americans; with the originating role that that latter series of photographs plays in the SFMOMA exhibition Public Information; the time has come, it seems for an accounting—as part of the general re-evaluation of the 1950s—of Frank's place in American culture, and of The Americans specifically as a cultural artefact. In that process, the book becomes a symbolic object that can be contested and used for various ideological purposes, according to its readings, as symbolic, if you will, as the American flag.

The most recent interpretations have tended to deflect the negativity of Frank's vision to only part of the book and to part of America. The book itself is thus divided negatively and positively, now along race and generation lines. Authors confirm the traditional findings of the vacuity of (white) Americans and their culture. They begin, however, to excavate a positive expression in another people and culture—that of Black America and popular music assimilable under the later rubric youth culture. As a beat fellow traveller, but not yet part of that inner scene during his 1955-56 cross-country trips, Frank could empathize with that alienated liberation.

Actually, these new interpretations began in the mid 1980s. So, in the 1985 article, "The photographer in beat-hipster idiom: robert frank's the americans," George Cotkin wrote: "The Americans offers, as I will demonstrate, a sustained critique of the barrenness of American culture, but along with his Beat and Hipster comrades, Frank possessed a vision of renewal and rebirth. He believed that the counter vision and lifestyle of America's black population offered a viable alternative for white America. Frank's presentation of black America, however, was not a naive celebration; it recognized the problematic nature of racial realities and the loneliness and alienation that afflicted all Americans."[4]

A year before in his book American Photography: A Critical History 1945 to the Present , Jonathan Green wrote:

The few moments of genuine energy he perceived within America were distinctly un-American. They came from a world beyond conventional expectations and attitudes, beyond the narrow alternatives offered by the establishment's culture. They came from the vitality of America's subcultures and countercultures rather than from the image Ginsberg saw on the television set. There is more human intensity, joy, meditation, and grief in the photographs of blacks than in the photographs of whites. There is more feeling emanating from the omnipresent jukebox than from the entertainments of high culture.[5]

These views are reiterated by Philip Brookman in the book for the 1986 Houston Museum of Fine Arts exhibition when he writes: “[The Americans'] overriding theme was the alienation and dissociation he found throughout the country. The book did point to a certain resurrection of culture among the American blacks he visited in the South and the ‘beat’ lifestyles he photographed when he met hitchhikers and motorcyclists on the road.”[6]

The theme is finally consolidated in Robert Frank: Moving Out by curator Sarah Greenough: "Frank not only described the 'somber places and black events,' but also those people, places, and things that seemed true and genuine, with a spiritual integrity or moral order. In The Americans he saw those sources of strength in the subcultures of music, symbolized most evocatively in the glowing jukeboxes, which often seem more alive than the people that feed them coins; in African-American culture and alternative religious groups, neither of which seemed choked by puritan values; and in the integrity of the family unit."[7]

This division of the book to mark its counter-values would leave white trash and white working class, on the one hand, and the middle and upper classes and politicians, on the other, to sustain Frank's original critique. The elderly, cowboys, destitute, working women (all categories of the white poor), would be victims of Frank’s cruel, camera portrayal, alienated in their own lives, and then stripped of their interiority made to stand for alienation in America as a whole. Blacks and youth culture, meanwhile, are redeemed as their subjectivity is given value.

In a sense, this division marks the obverse of the dominant interpretation organized in the 1970s and early 1980s as the contrasting relation between Walker Evans and Frank which appears variously in the writings of William Stott (1974), Tod Papageorge (1981), and Leslie Baier (1981). There the relation of black to white stands in the same value relation as that of Walker Evans to Robert Frank. To take one, negative, example:

What Frank shows us is a land of sullen people, bored, phlegmatic, nasty in their emptiness; a land in subjugation to prefabricated things and pleasures; a land of anomie where the television set and juke-box have replaced humans as the center of the energy of the room. Evans’ people, for all their reserve, were not passive before the junk of modern commerce; in a characteristic picture [Interior Detail, West Virginia Coal Miner's House, 1935] Evans showed how a West Virginian coal miner used a Rexall poster and a Coca-Cola Santa Claus to give some color and warmth to the cardboard walls of his carefully swept living-room. In Frank’s America [Ranch market—Hollywood] a plastic Santa above a diner counter becomes just one more piece of crud on the wall. The Santa smiles, but here only unreal people—plastic people like beauty queens and TV hostesses—smile; real people, like the waitress in the diner, have dead eyes and clenched teeth. Whereas Evans showed his people to be aesthetically respectable and thus morally worthy, Frank used his people’s lack of taste and vigor to condemn them; theirs is a true poverty, a poverty of spirit.[8]

Opposition here is neither race nor class based since Frank's condemnation is taken to be universal. A moral judgement is brought to bear not just on Frank’s vision but, more significantly, on the subjects of his photographs as well: Evans’ "people" are more “morally worthy” than those Frank photographed. I shall return to this description in another context. Needless to say, description is always already a judgement, but that responsibility is the writer’s alone, and the attribution of morality cannot be addressed to the photographer necessarily and certainly not to the subject. How can we ascribe an inner state based on an external look and this transitory record of the photograph? Unless the external structure of the book leads us to that belief and understanding of the photographer's intent.

It is not just a matter of determining Frank's attitude towards what he saw on his trips and his intention in the photographs. By the evidence of the photographs and his own words, I could argue both ways, of Frank as a nay or yay-sayer. It is rather the narratives of identification I am interested in, the manner in which, from the mid-1980s on, writers could split their identification maintaining part of the original judgements of reception—"we are not that"—while beginning to identify with Afro-American culture, by re-evaluating those images and exempting them from the first condemnation of the book. To re-evaluate only part of an interpretation while maintaining the rest, without thus realigning the context as a whole, needless to say is problematic. To make such a reversal for only some of the images implies the pure malleability of photographic meaning, a meaning, in the case of The Americans, determined, not by the single image, but by the structure of the book and the narrative series it initiates therein—as recurring themes or linked successions of images.[9]

What these later critics want to see is the inverse of what the earliest critics did not want to see and both read their own rhetorical apparatus into the pictures. Cotkin agrees with Stott’s characterizations, but reserves it for whites only, substituting sexuality for morality. "Whites Americans, for Frank, are the walking dead ... without sexual passion or suggestiveness" in contrast to "black sexual freedom and ... accompanying lack of sexual repression and inhibition."[10] The Americans for Cotkin was hip to the Beat vision and visual proof to Norman Mailer's "The White Negro" (published in Dissent in 1957 and in Mailer's Advertisements for Myself in 1959). "Blacks alone in The Americans show emotion, demonstrate deep feelings, appear free," which reiterates what Jonathan Green already wrote in 1984: "There is more human intensity, joy, meditation, and grief in the photographs of blacks than in the photographs of whites." Such a contrast is depicted not just in individual pictures but in the sequences of the book: "The simple dichotomy of black emotions/white unfeeling or black freedom/white slavery is communicated most clearly in the structure that Frank uses to organize his photographs."[11]

In the most recent interpretations, Moving Out's curator Sarah Greenough accepts the traditional four-part division introduced by the thematically recurring American flag but elaborates on the specific function and meaning of each section:

Each of the four sections addresses different aspects of Frank’s understanding of America and expresses a different feeling. Like a musical score, the first chapter establishes the themes the book will explore: the role of patriotism and politics, business and the military, African-American culture and racism, rich and poor, youth and religion in American society. The second, as Frank wrote to his parents, depicts “how Americans live, have fun, eat, drive cars, work.” The third presents those few areas of deviance and non-conformity, as well as the strength and vitality that Frank saw in Afro-American society, motorcycle gangs, alternative religious sects, young people and music. (Frank clearly aligned himself with these outsiders by placing a photograph of his shadow falling on the exterior of a barber shop’s screen door as the second image in this chapter.) The fourth section speaks of the alienation of the American people and their lack of physical and spiritual connection to either their cities and towns or to nature.[12]

Even a cursory examination of the book shows these themes, so-described, spread evenly throughout the different sections. For instance, there is a more sustained sequence of American car culture in part four than in part two; (black) bikers appear equally in "deviant" part three as "alienated" part four. How are we to read, as well, the different functions of the flags introducing each section, that fluttering, back-lit plastic flag, for instance, between portraits of Washington and Lincoln introducing the theme of deviancy of part three? While The Americans is set up by the four-part division, narratives are sequenced in portions. As W. T. Lhamon has written, "Robert Frank had to sequence carefully the images he found on his road for The Americans—and what controls that book is still up for grabs."[13] It is not so much, once again, an interpretation as a judgement that is at play here.

Still, Greenough can maintain the traditional interpretations when she claims that the rest of the book "speaks of the profound malaise of the American people during the 1950s. It reveals the deepseated violence and racism, and the mind-numbing roteness, conformity, and similarity of the ways Americans live, work, and relate to one another. It describes our symbols of patriotism as transparent and meaningless, our public celebrations as hollow, our religion as commercialized, and our politicians as fatuous or distant at best, and egomaniacal or corrupt at worst. It shows a country that despite vast wealth and a seemingly endless array of consumer products, admitted little real freedom of choice, expression or thought. It shows a country that plastered smiling faces on its walls and seemed to demand a universal optimism from its people, but was, in reality, joyless and depressed. "[14] We can ask: how does the book show both vast wealth and little real freedom of choice? How can it show the demand for universal optimism in a joyless reality? Is not this demand and description, instead, a projection from the present on the part of the author, a variety of moral attribution we saw earlier in Stott [and others]?

While a sequence of images may lead us to think we can identify Frank's themes, each single image functions, rather, as an emblem or a symbol with which we identify (condensing a narrative we begin in our own mind and bring to the image), much as we do with those political symbols of republicanism—the "reproductions" of Washington and Lincoln hung above the Detroit bar in the photograph that introduces part three—labelled as empty by Greenough. Like all symbols, they are empty only if we do not belong to the community they define. But at the same time, treated alone, these images are filled by the viewer's, or writer's, response—or ideological reflex. If such is the traditional role of the symbol, what is the new community of identification Frank portrays in a book which is taken to represent more than just a slice of time but to get at some essence of Americanness?

Can it be that the reason people project meaning onto a mute image, that potentially can sustain any interpretation while revealing none, is that Frank's photographs actually are about interiority [the look that hides the thought]? That it is the subjective vision which makes their subjects each, and in his or her own way (that also is shared in the same right), an American? And that each writer responds by what he or she think America is about—past and present? Such would explain why this book, The Americans, resonates particularly for each generation. Perhaps Frank set out not to criticize what he saw in America but to discover what Americans were becoming in this new era, and he pursued this vision non-judgementally because he, too, in the ontological sense, was becoming an American himself.

Trolley—New Orleans, 1955

***

Rodeo—New York City, 1954

Ranch market—Hollywood, 1956

Elevator—Miami Beach, 1955

“What I have in mind, then, is observation and record of what one naturalized American finds to see in the United States that signifies the kind of civilization born here and spreading elsewhere.”

Frank, Guggenheim application, 1954

“I am working very hard not just to photograph, but to give an opinion in my photos of America.... I am photographing how Americans live, have fun, eat, drive cars, work, etc. America is an interesting country, but there is a lot here that I do not like and that I would never accept. I am also trying to show this in my photos.”

Frank, letter to parents, Winter 1955

“I have been frequently accused of deliberately twisting subject matter to my point of view. Above all, I know that life for a photographer cannot be a matter of indifference. Opinion often consists of a kind of criticism. But criticism can come out of love. It is important to see what is invisible to others. Perhaps the look of hope or the look of sadness. Also, it is always the instantaneous reaction to oneself that produces a photograph.”

Frank, “A Statement...,” U.S. Camera Annual 1958 [15]

To offer a new interpretation of The Americans is to fall victim to the very reservations I outlined above—to create a portrayal of the writer's judgements rather than the work's themes. If the idea is to treat the book as a (quasi-) thematic whole ["fragments that make a whole"], we must restore that wholeness, bifurcated by recent readings, to the photographic subjects—the people, blacks and whites, that mainly comprise Frank's photographs. This is to be done on the problematic basis (for our time) of a subjective interiority. To achieve such a re-integration between the races would be to return to the "beat" interpretations that caused that division in the first place.

Kerouac, himself, of course, participated in such a reading in his glorification of black culture and the particular influence and model of jazz had on his prose style. He also set up the dichotomy of reversal of value between black and white when he wrote in On the Road:

At lilac evening, I walked with every muscle aching among the lights of 27th and Welton in the Denver colored section, wishing I were a Negro, feeling that the best the white world had offered was not enough ecstasy for me, not enough life, joy, kicks, darkness, music, not enough night.... I wished I were a Denver Mexican, or even a poor overworked Jap, anything but what I was so drearily, a "white man" disillusioned.[16]

That disillusion, however, was not counter-discriminatory as Kerouac/Sal Paradise was able to dig all sorts of beat characters such as white farmers, college kids, etc. We only need to look to Kerouac's introduction to The Americans itself. Compare Kerouac's description of the rodeo cowboy of Frank's Rodeo—New York City to that of Ian Jeffrey. Kerouac writes: "Tall, thin cowboy rolling butt outside Madison Square Garden New York for rodeo season, sad, spindly, unbelievable—," while Jeffrey, writing in 1975 of this photograph as a typical Frank parody: "In the fictive America the Westerner is a stalwart hero; in Frank's version he is street idler in cowboy dress..."[17]

Moreover, Kerouac puts the lie to Stott's evaluation of Frank's subjects such as the waitress in... Ranch market—Hollywood ("real people, like the waitress in the diner, have dead eyes and clenched teeth") in his closing comments on an analogous image, Elevator—Miami Beach: "And I say: That little ole lonely elevator girl looking up sighing in an elevator full of blurred demons, what's her name & address?" Why can Kerouac open himself and identify with these images others find reflected a degraded interiority?

Let's examine this image that Stott had contrasted negatively to another by Evans. This image turns out to be typical of a number of other in the book of individuals in social settings defined by signs and machines: Americans eating, living, and working. This was "the kind of civilization born here and spreading elsewhere," Americans living amongst their signs and their machines with a certain obliviousness that marks their interiority. How can we judge that interiority as a blankness just because of the subject's surroundings—a waitress in a greasy spoon or customers at their counter (Drugstore—Detroit), however much that outer life may have been transforming the inner? (The continual displacements of American society are not just the physical movements across the country that Frank himself recorded in his Guggenheim trips that made this book, but that take place internally as well.) This conflict and transformative impact of the outer on the inner and vice versa is emblematic of the problems of reading this book, of interpretation itself. This is the problem of, on the one hand, meaning being on the outside of the image rather than inside—the structure determining the themes, and, on the other hand, the narrative embeddedness of the themes in the images. Such a problem accounts for the varied readings The Americans has produced.

So attempts such as Leslie Baier to find a formal photographic effect for the interior alienation only account for half the problem because they repeat the assumption of a dead interior life: "Frank’s people, like Evans’ subway riders, seemed confused and apathetic, immersed in the private world of their own thoughts, or trapped in an alien world in which they are not allowed to function as thinking, feeling individuals."[18 ] Only one writer, W. T. Lhamon, seems to have recognized the moment Frank himself realized, transformative of the American self, which bases itself on that portrayal of the interior life.

In The Americans, Robert Frank recorded the precise moment of Americans discovering their difference: acknowledging and finding the means to step away from their colonized selves.... Over and over, the participants in Frank's photos gesture in at least one of two ways. They put their hands to their faces in vernacular versions of "The Thinker." And they look away, memorializing moments which, according to Jack Kerouac talking about an outtake from this series, showed "man recognizing his own mind's essence, no matter what." In both signals, their real gaze is inward, often with their eyes closed in public. These seeming signature gestures characterize not Frank's work as a whole, but this volume, these subjects at this time, ordinary citizens of the mid-fifties. They are a striking confirmation of provincials acknowledging the onset of their capital consciousness, for they enact it.[19]

In Frank's reply to his critics, he stated "It is important to see what is invisible to others. Perhaps the look of hope or the look of sadness." Perhaps this is all we can see in these photographs: a look which Frank identifies is of the interior. This look is not something we, nor the photographer, can know and about which the photographer does not make a moral judgement. "Criticism can come out of love," he added. Nor does it editorialize.

It was the double sense of beat—beat/beatitude—that Frank exemplified in his photographs and that Kerouac recognized. Not one or the other as a decision of meaning whereby the locus of value is given to blacks or whites. It is not an either-or, that to be for something means to be against another [the binary logic beats would rebel against]. That white trash and white workers are not necessarily maintained in the traditional meaning and trashed a second time while blacks are re-valued. White as well are "beatified"—given an interior life—in the way Kerouac recognized.

Kerouac understood very well that Frank's photos are American, "As American a picture—the faces don’t editorialize or say anything but 'This is the way we are in real life and if you don’t like it I don’t know anything about it 'cause I’m living my own life and may God bless us all, mebbe'... 'if we deserve it'...”

In turn, should we be editorializing on these images showing American becoming? How can one editorialize on being?

Jack Kerouac, Introduction to Robert Frank, The Americans

Notes

1. Robert Frank: From New York to Nova Scotia, p. 14.

2. Evans, Robert Frank: From New York to Nova Scotia, p.

3. Stott, p. 84

4. Cotkin. p. 19

5. Green, p. 89

6. Brookman, Robert Frank: From New York to Nova Scotia, p. 83

7. Greennough, p. 114

8. Stott, pp. 83-84

9. [Greenough's essay, after all is called, "Fragments that Make a Whole: Meaning in Photographic Sequences."] [meaning on the outside of image rather than inside] [Note: This is exemplified in Cotkin's narrative impulse linking five photographs in sequence in the middle of the book. (22-24) He accepts Frank's photographs in general "as a metaphorical foray into the pictorial representation of the Beat idiom," representations which, in turn, become Cotkin's metaphors for describing the images.]

10. Cotkin, pp. 25, 29

11. Cotkin, p. 26

12. Greennough, p. 113

13. Lhamon, Deliberate Speed (1990), p. 156

14. Greennough, p. 114

15. RF: From New York, p.20, p. 28 (translated from German), p. 31

16. Kerouac, On the Road, 180

17. Kerouac, Intro; Ian Jeffrey, Creative Camera...1975 in RF: From NY..p. 58

18. Leslie Baier, Visions of Fascination and Despair: The Relationship between Walker Evans and Robert Frank,” Art Journal, 41: 1 (Spring 1981), 57.

19. Lhamon, Deliberate Speed (1990), p. 19]

[n. 5, "The full remark appears on a postcard Kerouac sent Robert Frank: "Dear Robert--That photo you sent me of a guy looking over his cow on the Platte River is to me a photo of a man recognizing his own mind's essence, no matter what." Frank printed the message on the page facing his photograph in The Lines of My Hand."]

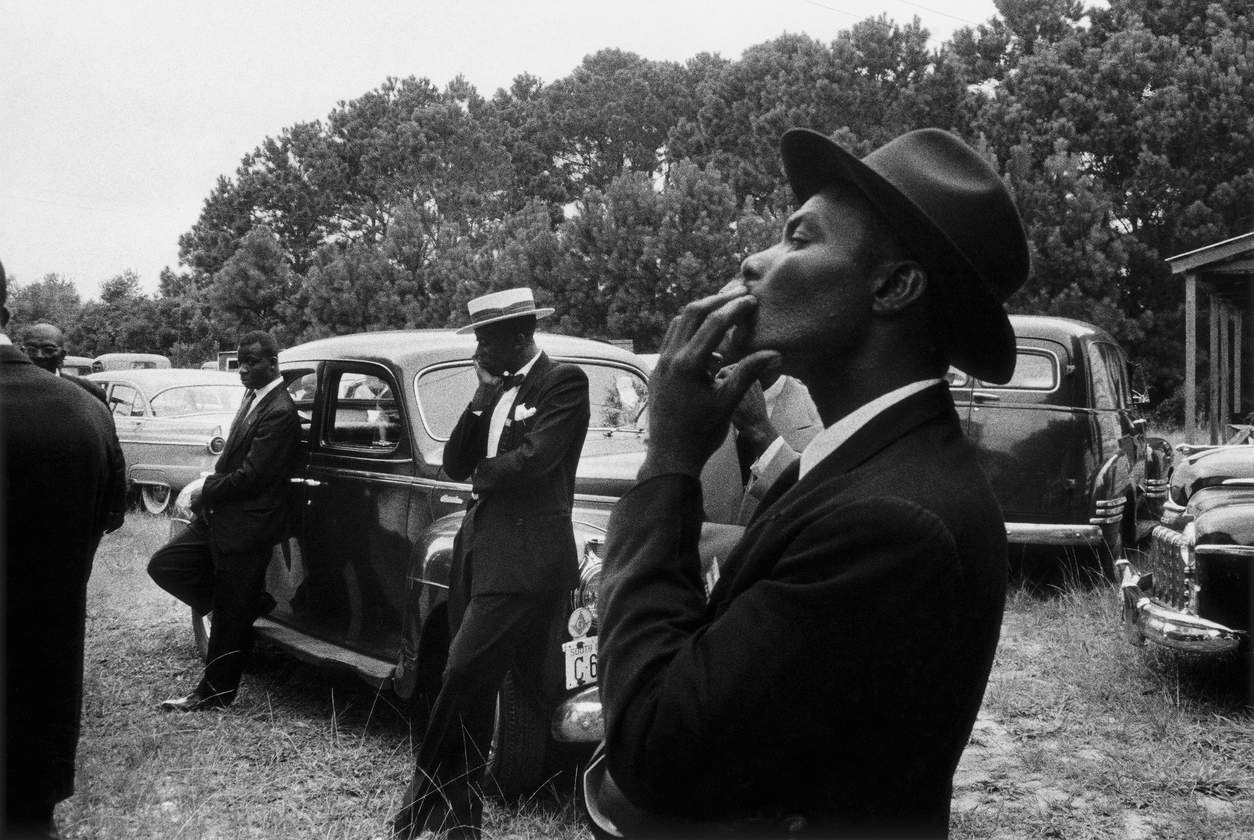

Funeral—St. Helena, South Carolina, 1955

Indianapolis, 1956